Introduction to the Inspiring Life of Author Mildred D. Taylor

Introduction You’ve probably read a few books in your lifetime. But have you ever read a book that changed your life? That’s what Mildred D.

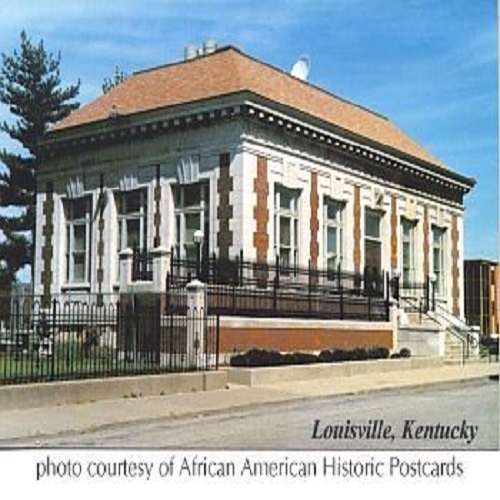

The Louisville Western Branch Library was the first public black library in the country to provide service and totally operated by Louisville black residents.

In 1905, even though slavery had been abolished 40 years, nearly all public libraries throughout the country were closed to African Americans. The Louisville City Council in 1902 mandated a decree for a public library system, which explicitly excluded the black residents. Black residents promptly challenged this exception.

Local educator and civil rights activist, Albert E. Meyzeek proposed that city council allow black residents access and usage of the new library system. The struggle was settled by the time the library system was schedule to open in 1904. A prototype now detailed a branch for African Americans, wholly subsidized by philanthropist Andrew Carnegie.

Thomas Fountain Blue was chosen as branch librarian. This course of action made him the first African American to head a public library in the United States. His vision was to create a community outreach approach. He did only wish to stock books, but instill a community of learning. He stated ” it forms a center which radiate many influences for general betterment. The people feel that the library belongs to them, and that it may be used for anything that makes for their welfare.”

The branch library did become a site of community. It included a children’s section responsible for organizing storytelling, discussion and specific events to aid the intellectual development of black children in Louisville. Once a year, Joseph S. Cotter, a local black educator would sponsor children’s spelling bees with prizes that consist of cup winners and cash rewards. Also, the famous Douglass Debate Club for high school boys was formed under the direction of Mr. Blue in 1909 to familiarize its members with (1) parliamentary practices, (2) to keep them updated with great topics and (3) train to speak in public.

The branch was under threat of closing, but in 2001 Prince secretly donated $12,000 to the Louisville Free Public Library to keep the branch open. The branch did survive and today houses the African-American Archives, which collects historical data on African-Americans in the Louisville, Kentucky area and throughout the country.

This historic landmark has a lot of values, stories and memories hidden in it walls-but it is only visible to the people who want to see things-see the world with justice and equality.

Introduction You’ve probably read a few books in your lifetime. But have you ever read a book that changed your life? That’s what Mildred D.

So you’re interested in becoming a podiatrist? That’s great! Podiatry is a fascinating and multifaceted field that can lead to a rewarding career. But before

If you’re not familiar with Sharon Flake, she’s a prolific author of young adult literature. Her books explore tough issues facing teenagers, from racism and

Hi, art lover! We wanted to introduce you to Shane W Evans, an extremely popular illustrator, and author. Evans was born in Columbus, Ohio, in